Triangles, me and a friend of mine used to joke, are the secret to everything. They can be found strewn across the world’s spiritual and cultural history like recurring tokens of a transcendent coinage – The Holy Trinity in Christianity, The Great Triad in Taoism, the three bodies of Buddhahood, the Enneagram Triads, The Pyramids of Giza, Chichen Itza, Meroë and elsewhere; two overlapping triangles make up the Star of David, four upwards-pointing triangles represent the Hindu god Shiva…. The number three is considered the most sacred number in most religions.1

But it wasn’t until I read a passage from René Guénon’s The Reign of Quantity and Signs of the Times that my own intuitions about the significance of the triangle crystalised into a solid idea. It was a roundabout kind of realisation, as the passage itself makes no mention of the three-sided things:

“Spherical or circular forms are related to Heaven, cubic or square forms to Earth… these two complementary terms are the equivalents of Purusha and Prakriti in the Hindu doctrine, which means that they are simply another expression for essence and substance taken in their universal meaning…”

Circles and squares, essence and substance. Ok, René, but what of the triangle?2

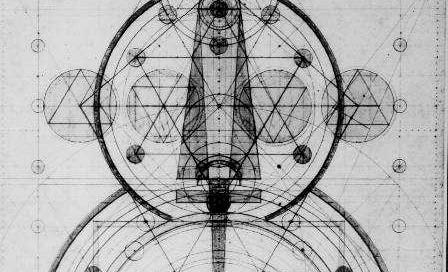

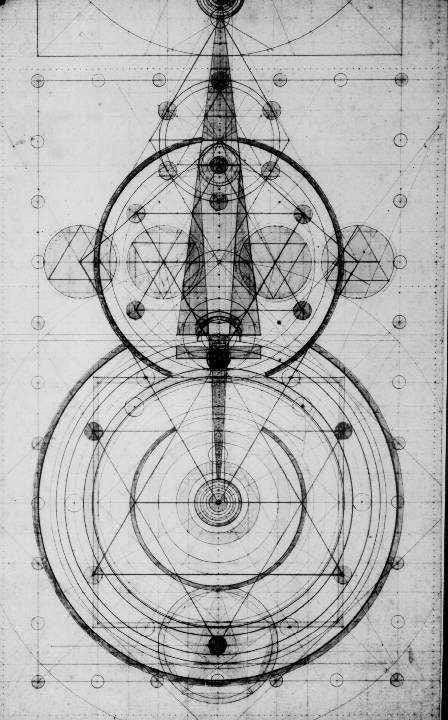

Before we rush to some precarious isoscelestic summit, we should lay some groundwork. To consider the circle first of all – in the perimeter of a circle every point, though mappable, is interchangeably undefined, therefore it contains in potentia all other shapes collapsed into an “unrealised” unity. A unity can also be represented by a straight line, in that it is self-existent and infinitely divisible, though symbolically it is not equivalent to the circle; it evokes a much more terrestrial set of associations, it is the ground to the circle’s sun. It also has directionality, whereas the circle is recursive. In sacred geometry, the split directionality of the straight line symbolises the duality of manifestation, while the ouroboric circle symbolises transcendent wholeness.

The straight line, therefore, is a unity that is nevertheless subject to the inherent division of matter, like a circle that has fallen and split itself open, pandora’s box-like. In a square, four straight lines are held apart as opposing faces. But, more than faces, do we not instinctively perceive these lines as forces?

I suspect that our appreciation for the simplistic beauty of geometry comes from a deep intuition about balance and harmony, rendered diagrammatically by the vectors of its shapes. “Music is liquid architecture and architecture is frozen music.” Said Goethe. Architecture is to geometry what the cube is to the square, and Schopenhauer, a great admirer of Goethe, says of architecture in The World as Will and Representation:

“…if we consider architecture merely as a fine art and apart from its provision for useful purposes… we can assign it no purpose other than that of bringing to clearer perceptiveness some of those Ideas that are the lowest grades of the will’s objectivity. Such Ideas are gravity, cohesion, rigidity, hardness, those universal qualities of stone, those first, simplest, and dullest visibilities of the will, the fundamental bass-notes of nature; and along with these, light, which is in many respects their opposite. Even at this low stage of the will’s objectivity, we see its inner nature revealing itself in discord; for, properly speaking, the conflict between gravity and rigidity is the sole aesthetic material of architecture; its problem is to make this conflict appear with perfect distinctness in many different ways…”

Solid bodies in space can only take form in the vicinity of a gravitational pull, for what are solid masses if not the objectified will to resist gravity’s urge to compress? Rigidity is resistance to gravity – the will not to be crushed, the will to rise, to expand, and in doing so to take shape. From our instinctive understanding of this natural conflict of forces comes the aesthetic component of geometry.

Light, however, which is the prerequisite for any aesthetic appreciation, plays no part in geometry, or at least cannot be represented by means other than secondary lines which evoke nothing of the experience of light. But, as Schopenhauer says, light is in many respects the opposite of “gravity, cohesion, rigidity, hardness… those first, simplest, and dullest visibilities of the will.” So for the sake of illustration, let us step away from the square into the world of three dimensions and consider the play of light upon a cube. If we have a single source of light falling upon one face of a cube its corresponding opposite will necessarily be in darkness. The only way to cast a light from a single source onto two opposing sides is by means of reflection.

The association of light with the intellect is so widespread that it needs no justification – if we are clever we are bright, our thoughts are illuminating, with erudite words we dazzle. The chambers of the human mind are like darkened rooms through which the bright circuits of the intellect tear. So to supplant the symbolism of the square/cube onto psychology – reflection can be synonymised with metaphor, the bringing together of two distinct things under a unifying idea. In the most sublime cases (one measure of a great writer is in the boldness or surprisingness of their metaphors), two diametric opposites can be brought together by the connective power of the mind. A unification. A kind of linguistic performance of the yin-yang symbol.

Not all metaphors have to aspire to the dissolution of opposites though – the beauty and endlessness of metaphor is owed to the fact that the object of its play is no mere six-sided cube, but a veritable apeirogon, infinite sides all alightable – the 10,000 things spoken of in Buddhism and Taoism. All of manifestation, essentially, or at least all of it open to our perception. There is no end to the possible performances of metaphor, all of which pull back the curtain just a little on the unity behind the stage.

In my university days, before I was able to express it rationally to myself, I felt the sublimity of metaphor in my bones, and wrote a gigantic YES in the margin when I found this in one of my course-appointed texts, The Art of Fiction by John Gardner:

“We are moved by the increasing connectedness of things, ultimately a connection of values.”

I took it as good literary advice – I had dreams of conjoining in feats of poetic prose such disparate items as the moon and a baby’s tooth, a scabbard and a mineshaft, a dewdrop and a butterfly…. But now I see that Gardner’s statement goes beyond objects themselves, and points towards the fundamental unity behind all things. The circle onto which the apeirogon is plotted.

We have mentioned the circle, the straight line, the triangle, and the square. But between the circle and the triangle we have another shape consisting of two lines, or, arranged as we are probably most accustomed to seeing them: a cross. If we render the cross in three dimensions, then we can envision it as the geometrical map that takes us from sphere to cube – the skeletal or structural work that allows us to pass from the infinite and formless essence to the delimited and solid substance. If the cross represents this shift materially, then the triangle could be said to represent the same shift in reverse, from substance to essence, but this is a temporal shift (or, perhaps, anti-temporal). To explain this, we’ll have to consider the symbolism of the triangular and the cubic in the corporeal world.

Symbolically, triangles represent an upwards movement (or downwards if they are inverted). They signify a change in state, a journey from two separate points to a unified one. Think of the heroic, transformative narrative of climbing to a mountain’s summit. This achievement, considered superficially, connects the climber to the summit, and lifts them to a great elation, or, as the Scottish mountain walker and writer Nan Shephard says in The Living Mountain (with poignant phrasing as far as our consideration of triangles goes), “it intensifies life to the point of glory”. Because of the singular power of the mountain summit, the language of the mountain has been grafted onto the language of the inward journey – there are summits inside of ourselves to be climbed, psychic twins of the lofty peaks to which mountaineers aspire. Really, even for the mountaineer, it is the inner slopes whose knowledge we truly seek. To quote Nan Shephard again:

“[The Cairngorm Mountains’] physiognomy is in the geography books – so many square miles of area, so many lochs, so many summits of over 4000 feet – but this is a pallid simulacrum of their reality, which, like every reality that matters ultimately to human beings, is a reality of the mind.”

To climb a mountain is the archetypal emblem of overcoming, of transcendence, of standing aloft from the world of matter below, ascending to the airy heights, away from the multifariousness of the earth to the unity of sky. In classical elemental terms, it is a journey of sublimation from earth to air. In some forms of alchemical symbolism, earth is represented by a square; substance, and air by a circle; essence. The mountain is, of course, triangular.

Fire, fluidly triangular in reality, is the element represented by the triangle. Fire is the sublimating agent – it is heat that transforms matter into different states. Fire tends upwards, burning from a base which it destroys in order to rise. Its destructive act is the transforming of solid into gas. Water is often represented by an inverted triangle, and it can demonstrate this changing of state in reverse – vapour becoming liquid, liquid freezing into solid. Natural manifestations of the inverted triangle only occur in dark and cold places (i.e. places away from the heat and light of fire), such as the stalactites or hanging icicles in caves.

Cubes or squares, in the real world, tend to imprison or contain – think of cages, boxes, buildings. They are inherently a bordering shape, and a shape in which none of the sides that gravitationally want to meet do meet (the vertical sides keep the horizontal from collapsing into each-other). But here’s the trick: the triangle can be envisioned as the removal of the “lid” from the top of a square, so that its two opposing vertical sides collapse inwards to join at the summit. As long as this extra line of separation exists it creates two sets of opposites: the above and the below, the right and the left. Directional opposites. There are three directions that can be measured in geometric space – height, depth, and width. But extract the fourth line from the square and it becomes the line of that transcendent and irreversible direction: time.

Because, metaphysically speaking, time (with space in tow) is the wedge that keeps everything apart; it reveals each to the other, it is the very essence of separation. Yet it is in and of itself transcendent from matter and does not have any direct effect upon it,3 as Schopenhauer explains in Volume 2 of Parerga and Paralipomena:

“If time inhered as a quality or accident in things in and of themselves, then its quantum, its length or brevity would have to be able to change something in things. Only it is completely incapable of doing this; instead, it flows over things without imprinting the slightest trace on them. For only the causes in the passage of time are effective, by no means the passage itself… It is therefore the same absolute ineffectiveness of time that appears as the law of inertia in the mechanical realm. If a body has once been set in motion, then no time is capable of stealing or even just diminishing it; it is absolutely endless if physical causes do not work against it, just as a resting body rests eternally if physical causes are not added to set it in motion. Already from this it follows that time is something that does not affect bodies, indeed, that both are of a heterogeneous nature insofar as the reality attributed to bodies cannot be conferred upon time.”

Because time stands above the division of matter, it knows nothing of opposing forces. It is the transcendent, self-existent “force” which allows all others to become manifest within itself. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad claims that:

“Time is the womb of all that is born. It is the father of all that is created. It is the sustainer of all that exists. It is the destroyer of all that ceases to be.”

When we remove the line of time from the square to make the triangle, the two lines fall inwards to balance against each-other. We understand this because the concept of balance comes from the behaviour of physical objects, the knowledge of which, as Bergson explains, is our bread and butter. This means, however, that the nature of balance also cannot be conferred upon time. Time does not sustain balance, in fact it is the ultimate agent of unbalance. And yet when time is removed, and we examine the solitary line or the circle in isolation, they are the very emblems of balance.

If we are to seek balance in our lives and our societies then a certain degree of transcendental thinking is necessary – because it must be acknowledged that what we are striving for will not be found in any particular time-bound moment, but must instead be aggregated or approximated over a stretch of time. We cannot fall for the illusion of the perfect life. Utopia is a frozen image – unfreeze it and something undesirable will surely happen, somewhere, almost instantaneously. Nevertheless, it seems to be in our nature to strive towards this approximation, and we find our nobility in this struggle.

But to return to the image of the triangle (the square minus time, substance becoming essence); the Buddhist philosopher Nāgārjuna teaches that the middle way is the best way. The middle, reconciled symbolically as the summit in the triangle, cannot be reached in the square. Its point does not exist in the framework of such a shape. This is why the square represents the corporeal world of the Earth – the essential, unified centre is made non-existent by the force of separation (time) inherent in the shape.

Time is the medium within which we experience life. Therefore, bound to it as we are, we cannot find the centre by means of any “positive” postulate or pursuit, it must instead be glimpsed through the “negative” pursuit of the removal of the square’s ceiling. It must be sought in conceptions outside of time – which effectively results in the negation of the temporal, corporeal world. To try to reach the essential by the positive route, to seek within the world of time, is literally to scour an arena for something that exists outside of its walls. If we want to experience our own summits then the best we can do is to engage in pursuits that help us forget the passage of time – whether that is writing, meditation, mountaineering, martial arts, deep conversation, caring for a pet… anything that you feel provides a means for you to feed your soul. The mind knows only time, but the soul is wiser. If the intellect is a square, then the soul is a triangle. Bring yourself fully to your chosen pursuit, and, for some moments at least, you might escape the cage.

As a further illustration of the process of transcendence by which we might conceive of the joining at the summit that the triangle symbolises, we could consider the maverick mystic George Gurdjieff’s Law of Three, which he named as “the second fundamental cosmic law” applying to everything in the universe. He believed that every phenomenon consisted of three separate forces. In Season 2, Episode 3 of the podcast Gurdjieff: Cosmic Secrets, we get this summary of the Law:

“The higher blends with the lower in order to actualise the middle, and thus becomes either higher for the preceding lower, or lower for the succeeding higher. This is otherwise known as the Triamazikamno, consisting of three independent forces: positive, negative and neutral. And the phrase itself literally translates from Greek as ‘three I put together.’

Blending is intrinsic to the Law of Three; everything blends on every level, from matter and material, to ideas and mind. For instance, to make bread you must first blend flour and water. There are many ways to blend flour and water – you can use more water than flour, and instead of getting dough you will get a runny paste… To make dough, you need to use the right proportions of flour and water. Once you have the right proportions, you only get dough if you then blend them, and blend them, and blend them. It is called kneading, and you have to keep kneading it until it reaches the proper consistency. Then it will be ready to receive another force: the force of the hot oven… A transformation then takes place, and the dough turns into bread. After which, more blending can take place. You can blend the bread with a knife, and cut it into slices. You can blend the bread with butter or jelly. You can blend the bread with caramel drizzle, or sugary sprinkles. But it will not fulfil its purpose unless a third force enters, which will be another kind of oven, one that can transform the bread even further – the oven of a man’s stomach. With all three forces, the flour and water will fulfil their highest potential…

If we look, we can see three forces everywhere. In Christianity, they are the Holy Trinity: Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. In Hinduism they are Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva. In Chemistry they are found in atoms as protons, neutrons, and electrons. In particle physics, we find three quarks. In visible light we have three primary colours. And in music there are three notes in a chord.”

Linguistically, too, three-word sentences are the shortest possible sentences in which an object and a subject can be connected by a predicate. Ferdinand Kürnberger, famously quoted by Ludwig Wittgenstein in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, said:

“…whatever a man knows, whatever is not mere rumbling and roaring that he has heard, can be said in three words.”

Mapped onto a triangle, three-word sentences show the connecting of two points by a third, which exists above them, and so represents the successful marriage of the two by a transcendent element. “I am alive” – am (the pure expression of being) connects the self to life. “I will die” – will, in this case acting as the stand-in agent for time, connects the self with death, or mortality. “I love you” – love as the expression of desire connecting two separate beings. Desire and time together sit at the base of subjective experience, of which life is the summit.

Just like fuel and oxygen are needed for the element of fire to emerge, an object and a subject need a predicate before they can be synthesised. Two-word sentences such as “I am” or “I will” remain in the abstract without an object to act as a fuel to transform them into statements of determinable action. If we want to make statements that can bind two elements of the physical world, three words is the minimum that we need, and the more words that we use the more prone to muddying the waters of clarity we become, just as shapes become harder to process the more complex they become.

Kürnberger knows that statements of practical knowledge begin with three word utterances, and are rarely made more certain with more (the game of philosophy is perhaps to challenge this rule, though, as Wittgenstein found out, it often ends up proving it). “I will run” is a clear statement of intent. “I will run fast” invites relativity and dispute (just as adding the extra line to the triangle to make the square adds relativity, i.e. time, to the equation). Time determiners such as in “I am happy now” are redundant and add nothing to the statement “I am happy”, since am already implies the present moment. Negations such as “You must not drive” or “We can not win” are subordinate to the positive three-word sentences that they negate.

Statements of transition such as “I am becoming old” are instances where English grammar might betray the triangular purity of such sentences, since am and becoming are both statements of being and, taken in an independent context, can essentially be considered synonyms. Grammar is variable and inconsistent, but geometry isn’t – though it is poetically satisfying that adding the word becoming to the above sentence not only gives to it a fourth word, but introduces the passage of time into the concept; becoming is explicitly an expression of time’s movement. It makes the sentence a neat linguistic analogue of how, once the line of time is reinserted to make the square, time must necessarily disguise itself as just another of the four spatial lines. In our sentence it does this by borrowing the nature of the word am – both am and becoming are expressions of time, but now that both of them are present simultaneously duality and division is implied, and the transcendent unity of time disappears without a trace.

Likewise, the transcendent experience symbolised by the triangle bypasses material uncertainty to provide direct illumination (i.e. feeding the soul). But reinsert the line and the matter-heavy square suddenly falls into existence. And just like that, like tearing open a portal – even though, really, we have just closed the lid of the box – variety and uncertainty abound.

And a magic number by hip-hop trio De La Soul.

Guenon does make mention of triangles elsewhere, most notably in The Great Triad. But I have not read that book, and it was the quoted passage from The Reign of Quantity that set off the train of thought that follows.

I’m picturing the separated line beside the triangle, like a staff in the grasp of a wizard dressed in a cartoonishly triangular robe.

Thank you for that delightful reduction of mountain climbing to “climbing triangles”. Gave me a good chuckle. If only these essays were on the printed page! I keep feeling the impulse to make notes in the margins, but the screen re-emerges.

All of your essays recently have been a reminder that I need to read Schopenhauer. Would you recommend ‘The World as Will and Representation’ for a first-timer?