It has rained a lot this year. I wake up, turn over, and look at the sky through the roof window in my bedroom. Every morning grey. Most afternoons too. Small differences; Morning Ash, Afternoon Zinc. My flat has two roof windows and when I leave the doors open they send the sound of the rain pattering through all of the rooms. The building is old and sometimes the roof leaks, always in a different place. Patched up, it breaches somewhere new. My Tropical Teal wall is streaked Metallic Seaweed in two places.

A legacy of dreary, drizzly days has been long endured in the UK. No monsoon season here, but weeks on end of tin-grey cloud coverage and persistent dampness are liable to insert themselves into any of our seasons. We’re relatively sheltered from extreme conditions, however, which gives us a kind of Stockholm syndrome pride in our rain – like it’s a mildly annoying acquaintance whose company we’ve come to begrudgingly enjoy because they always give us something to talk about. Our rain is not often violent and disruptive, as it was for those unfortunate enough to be caught in the recent floods in Valencia and Florida, though we are of course not entirely strangers to flooding either – something that will only become more common with warming seas and major disruptions in the Gulf Stream.

All weather conditions can reach a degree of potency at which they become destructive. But on the body of the earth the UK is perhaps an elbow – relatively small, sturdy, often on display, mostly insensitive, somewhat calloused…1 We don’t take the brunt of the damage, though we’ve certainly been known to dish it out. This is not a critique of the UK, though, so I’ll stop with the elbow metaphor before it becomes the entire essay. The point at hand is that we are fortunate to experience little in the way of extreme weather, but when it comes to persistent rainfall, we’re one of Europe’s wettest.

I’ve spent many hours watching it rain.

Like silence, and like distance, rain is a phenomenon that encloses a portion of the world within its zone of influence, and alters the aspect of everything within that zone. Most often we perceive this zone from within as a totality of coverage, but there is something implicitly awe-inducing in seeing from a distance the entire perimeter of a spread of rain – we see finite edges visible to our eyes but alien to our experience.2 So when we witness the full nebular operation of a cloud at work it does not evoke the sensation of being inside of the rain; instead, it offers us some minor referent of what it might be like to glimpse our universe from the outside. Because being within the rain is to be within an entire world. In Water and Dreams, Gaston Bachelard says:

“The first to be dissolved is a landscape in the rain; lines and forms melt away. But little by little the whole world is brought together again in its water. A single matter has taken over everything.”

When a single matter has taken over everything, everything is equally lustred with significance; the air itself is palpable, the raindrops descend like tactile wires transmitting one single terraqueous mode of existence to every creature and object residing under their cloud.

Picture a set area of the earth’s surface and everything on it as the bottom integer in a fraction, and a symbol of the sun as the top integer. Now swap the sun symbol for a raincloud – the value of everything changes. And there is an inner transmission too, a sympathy that passes between us when we watch someone struggle through the rain, or see a stray dog with wet, matted fur curled up in its found shelter. The rain is a universal struggle that we all understand; the waterweight of the world, an exterior malaise that stands in like an analogue for our interior burdens. Gabriel García Márquez (who is from Colombia, the rainiest country in the world, so if anyone should know about rain it’s him) gives us a very literal example of this in The Autumn of the Patriarch, when the General, pining for his lost love Manuela, looks out from his balcony “watching Manuela’s rain fall.”3

But – again like silence and distance – rain is a changeable and multifaceted phenomenon that can be experienced and envisioned in many ways. Ever since reading as a child Terry Pratchett’s description in Equal Rites of a storm that “walked around the hills on legs of lightning, shouting and grumbling” I like to imagine weather as animalistic – the wind a howling protest against things beyond our ken, snow a settling on of fur, drought a landscape stretched out on the dry tongue of a supine lizard.

The rain is clumsy, it thunders around and sets things spilling. It makes the gutters run. Within its threatening atmosphere objects withdraw into glowing behaviour, like children at school lined up to be inspected by a grumpy headteacher. Letterboxes berry-red and gleaming, fences straight, damp and dutiful in wet mud, lampposts abashed by their own height, illuminating with their downcast glance a small segment of rain like the tears of a private penance. Activity quietens because the world itself is active. Hush – the sound of the rain. It comes like an inspector, and the things of the world adjust themselves under its gaze.

But rain cannot inspect the whole world at once, so it draws the horizon in, seals us in its hermetic chamber, where the windows run and the roofs chatter. Within this new, miniature world everything wears a different face, and there are mysteries that form like little fungi fed by the novel atmosphere. Lesser mysteries perhaps; domesticated mysteries whose titillating secrets might even be discoverable, as if a section of the world has been partitioned off to engage in some minor play of small-scale life. The backdrops of faraway vistas and adventurous landscapes are retired. Like tulips we turn inwards when it rains. The rainy black-and-white nights of a noir hint at locked desk-drawers, shadowy corners, rooms behind curtains… always the interior holds the promise. “…human beings [are] great dreamers of locks…” says Bachelard in The Poetics of Space. If there were no mystery in the world it would be necessary for us to invent one.4

Rain makes nesting dolls of interior spaces which in more agreeable weather might seem outwards facing. The spider clinging to the underside of the kitchen counter enlarges its presence. The outside world becomes something else, blurred and impressionistic – something hiding itself. But this ring of hiddenness is exactly the lure that draws those of us who hear it – some of us bodily, most of us in imagination only – out into the rain. The inner reaching hand that I spoke about in There’s No Door Into the Mansion comes alive in the rain. Outdoor physical tasks are excused or postponed, or if not then they are given extra weight, preparations are taken. But it is those who stay inside who are the focus of the first part of this essay; those behind windows, beside fires, wandering the inner planes to the sound of the sky’s millipede patter. Wandering, perhaps, in search of the centre of the world, because nothing in the rain-space is far away. Everything discoverable is close at hand.

The dream world expands as the outer world contracts – but it expands downwards, which, as discussed in my post The Square Minus Time, is the direction, symbolically and actually, in which water tends (this is not an absolute rule, but most daydreams begin in inertia, and to dream upwards in the rain is a much more active pursuit that demands a surge of vitality from the dreamer). Crucially, in its expansion the imagination does not lose its sense of containment – as the dreams of freedom in the sleep of those imprisoned might carry, however lightly, the knowledge of their confinement – it is still fed by that single matter that has taken over everything. It is that single matter that has dictated its direction, its burrowing. In his fantastic 2022 novel My Mind to Me a Kingdom Is, Paul Stanbridge plumbs a similar intuition:

“But what can lie at the centre of an undifferentiated mass? Perhaps some unimaginable crystal structure eternally forming in no-time. Has our earth grown a pip or seed, a veritable centre to itself, an axis, stump, root or omphalos?”

Of course, wandering in the rain we wouldn’t really expect to stumble upon some crystalline growth or mysterious stump in the middle of the street, or tucked away in an alley, or incongruous in someone’s front garden – but would it surprise the fairytale parts of our mind if we did? Would it surprise our subterranean imagination if the intangible things in search of which it digs were suddenly unearthed, fantastical evidence of its fantastical labour? Inside – sheltered from rain’s reality, dreaming its dream – we are free to imagine that such things might appear.

Rain makes the world bodily, but the body it gives to it is fluid, so everything becomes a little more fluid, including causality itself; the stuff of reality loosens like drops on a windowpane, the imagination balloons bloated into the real. This is why board games have always been popular in rainy weather – apart from the simple fact that they can be played inside, they provide easy, and communal, access to fantasy. They allow families or groups of friends to indulge in the mostly unconscious sense of reality slippage, to give that vague impression the framework of a game to shape itself on. The game itself reveals nothing of its true shape to the outsider, only the words left on a finished Scrabble board, or the placement of the remaining chess pieces after checkmate, hint at what dreams hovered in the collective cloud-bubble summoned by their players. Other tabletop games such as Dungeons & Dragons or Warhammer explicitly require a collaborative dream-building project.

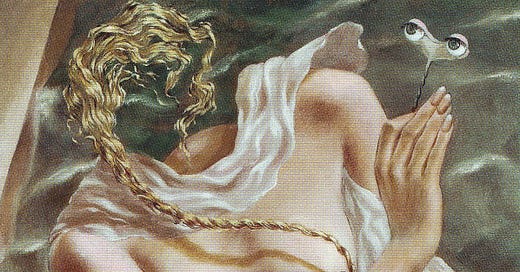

There are dreams that can be shared and dreams that can’t. Art is, perhaps, the practice of sharing the dreams that can’t. How many great works of art owe to a rainy day the dream that seeded them?5 We can never know, but solitary dreams in rain plunge deep, as if the soil of the imagination has softened too. In The Poetics of Space Bachelard relays to us a prose poem about a casket by Charles Cros, which illustrates perfectly the kinds of imaginary adventures we are capable of taking into the interior of things:

“…the poet carries on where the cabinet maker left off. Beautiful objects created by skilful hands are quite naturally ‘carried on’ by a poet’s daydream. And for Charles Cros, imaginary beings are born of the ‘secret’ of a marquetry casket.

‘In order to detect its mystery, in order to go beyond the perspectives of marquetry, to reach the imaginary world through the little mirrors,’ one had to possess a ‘rapid glance, fine hearing, and be keenly attentive.’ Indeed, the imagination sharpens all of our senses. The imagining attention prepares our attention for instantaneousness.

And the poet continues: ‘Finally I caught a glimpse of the clandestine festivity. I heard the tiny minutes, I guessed the complicated web of entanglements that was being woven inside the casket. The doors open, and we see what appears to be a parlour for insects, the white, brown and black floors are seen in exaggerated perspective.’ But when the poet closes the casket, inside it, he sets a nocturnal world into motion.

‘When the casket is closed, when the ears of the importunate are stopped with sleep, or filled with outside noises, when the thoughts of men dwell upon some positive object, ‘Then strange scenes take place in the casket’s parlour, several persons of unwonted size and appearance step forth from the little mirrors.’

This time, in the darkness of the casket, it is the enclosed reflections that reproduce objects. The inversion of interior and exterior is experienced so intensely by the poet that it brings about an inversion of objects and reflections…

In reality, however, the poet has given concrete form to a very general psychological theme, namely, that there will always be more things in a closed, than in an open, box. To verify images kills them, and it is always more enriching to imagine than to experience.”6

Here I take the word “enriching” to mean something like “adorning” or “adoring”, rather than championing any real superiority of sedentary imagination above active experience. Bachelard is helping us to see, throughout all of his work, how the imagination expands and decorates reality, persisting as a kind of fantastical mirror realm that is both alongside it and within it. He is perhaps the ultimate rainy-day writer.

Rain is to the sunlit world what night is to day, what shadow is to light, what Finnegan’s Wake is to Ulysses. Things change and identities blur. Even the days become indistinct in long periods of rain, as Gabriel García Márquez describes in Monologue of Isabel Watching it Rain in Macondo:

“What should have been Thursday was a physical, jellylike thing that could have been parted with the hands in order to look into Friday.”

In Márquez’s most famous novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude, it rains for four years, eleven months, and two days, and during this time the debaucherous Aureliano Segundo stays home and reads old encyclopaedias to his grandchildren, while his wife Fernanda “really believed that her husband was waiting for it to clear to return to his concubine.” But instead, his sex-drive diminishes and ultimately it is the rain that leads him away from his wild youth and settles him into old age:

“Occupied with the many small details that called for his attention, Aureliano Segundo did not realise that he was getting old until one afternoon when he found himself contemplating the premature dusk from a rocking chair and thinking about Petra Cotes [the aforementioned concubine] without quivering… the rain had spared him from all emergencies of passion and had filled him with the spongy serenity of a lack of appetite. He amused himself thinking about the things that he could have done in other times with the rain which had already lasted a year. He had been one of the first to bring zinc sheets to Macondo… simply to roof Petra Cotes’ bedroom with them and to take pleasure in the feeling of deep intimacy that the sprinkling of the rain produced at that time. But even those wild memories of his mad youth left him unmoved, just as during his last debauch he had exhausted his quota of salaciousness and all he had left was the marvellous gift of being able to remember it without bitterness or repentance. It might have been thought that the deluge had given him the opportunity to sit and reflect and… had awakened in him the tardy yearning of so many useful trades that he might have followed in his life and did not; but neither case was true, because the temptation of a sedentary domesticity that was besieging him was not the result of any rediscovery or moral lesson. It came from much farther off, unearthed by the rain’s pitchfork from the days when in Melquíades’ room he would read the prodigious fables about flying carpets and whales that fed on entire ships and their crews.”

Rain is reading weather, mending weather, napping weather – it encourages sedentary pastimes, pastimes that allow the mind to take precedence. It is the weather of reverie, fixing eyes myopically on windows and not the world beyond. Reflective weather. Reverie is reverence turned inwards. It is important that we don’t let our times of reflection be taken from us. A person who doesn’t dream does not know themselves.

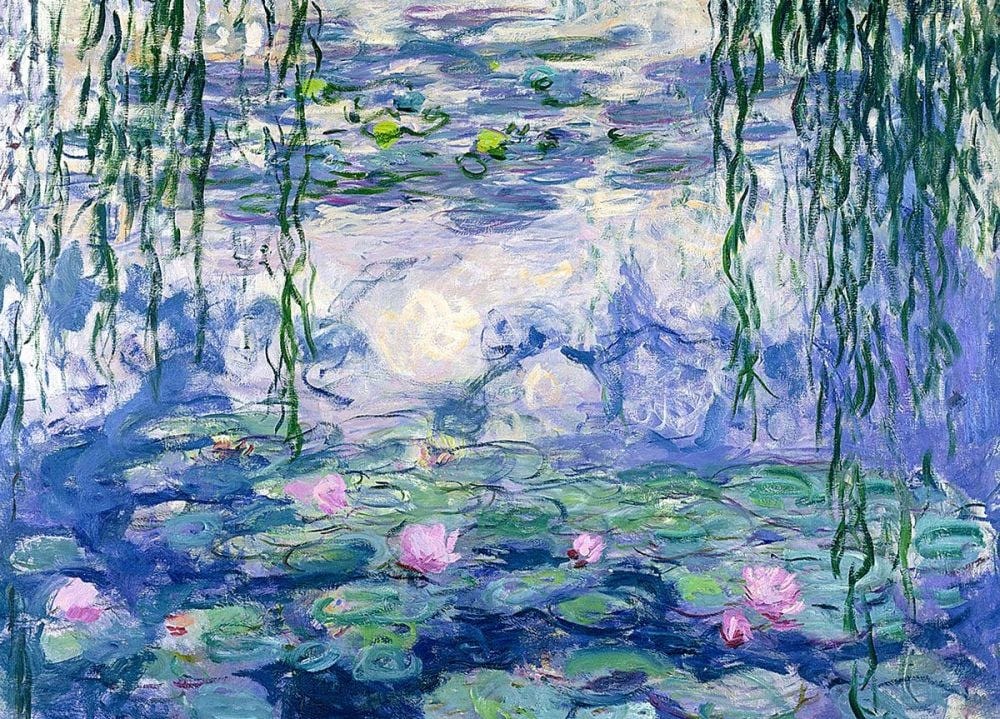

If there is any artform that can come closest to capturing the dream of the rain world itself, it is watercolour painting. The very material of the work, the paint, is mixed with water, just as when it rains everything beneath the clouds gets wet. Not all watercolours aim for this effect – as in any artform, a majority of its artists either eschew or fail to understand the unique affordances of their medium, and many watercolourists attempt to be more straightforwardly representational, in line with more conventional painters – but there are those great watercolours that revel in the element of their substance, and capture the landscape in its distortion, its transformation, its water-aspect. They reveal to us a world all but intangible outside of these works, a world only summoned by specific conditions which are not typically suited for prolonged looking. For the imaginal vantage of one of these watercolours to be viable, the artist must place themselves outside of the landscape, outside of the rain, where they can see it whole and not themselves be captured. Unless as a novel experiment, even the least sensible painters don’t paint in the rain; they must carry the impression back to the easel – and of course it blanches and blemishes in the memory. Great watercolour painting, therefore, works just as much with reverie as it does with water and paint – it is a window-gazer’s art. Its landscapes are submerged reflections of landscapes, as in a pool of water. Their worlds are seen as if “the sky’d been breathing on a mirror” – to quote the astoundingly beautiful Emily by Joanna Newsom.

Some examples:

Water and dreaming are inextricably bound up in our imagination because we begin our lives submerged in water in the wombs of our mothers, and since we can’t recall the inner life of our unborn and still-developing brains, what state of existence can we but help imagine when we see a foetus than one of dreaming? The foetus is the emblem of sleep – the one period of true hibernation in our human lives. The foetal position – ultimate repose. And rain is like a primal memory; the wet world, the world closer to how we might have expected it to be had we been able to anticipate a world at all before emerging into one. Rain is not strictly evocative of the womb in the sense that it does not actually plunge us underwater, but it does return something to us – we forget how much of the world is water, how much of us is water. Rain returns us to our dominant element.

We dream when we watch the rain. We go to the sea to dream. Our interiors are reflected better in water than in stone. We are fluid, changeable creatures, complacent in our illusions of solidity. Our foundations are not the concrete and mortar of our cities. Our natures are not as robotic as our enforced routines make them seem. We have more in common with plants than with robots, especially if we consider the separate organs and components that make us up, each persisting in its own vegetative life-process. Henri Bergson reminds us of this in Creative Evolution:

“The organised elements composing the individual have themselves a certain individuality, and each will claim its vital principle if the individual pretends to have its own… An organism such as a higher vertebrate is the most individuated of all organisms; yet if we take into account that it is only the development of an ovum forming part of the body of its mother and of a spermatozoon belonging to the body of its father… we shall realise that every individual organism, even that of a man, is merely a bud that has sprouted on the combined body of both its parents.”

Fittingly for the theme of the book, he uses this conception of the human being to subordinate the individual to the general current of life:

“…life is like a current passing from germ to germ through the medium of a developed organism. It is as if the organism itself were only an excrescence, a bud caused to sprout by the former germ endeavouring to continue itself in a new germ. The essential thing is the continuous progress indefinitely pursued, an invisible progress, on which each individual organism rides during the short interval of time given it to live.”

This is how we think of plants. Do we (most of us) mourn their death when they inevitably disappear? They will be back in the spring. They are never really gone. How often do we think of a new leaf on a familiar tree as a different entity to the one that occupied the same spot last year? How often do we contemplate the millennia of dead flowers the ground beneath our feet has swallowed up when walking through a living meadow? In this sense, we are no different from the plants – in the stems of our bones and the sap of our blood and the flowers of our organs – we, too, need water and sun and nourishment to thrive. And yet, for all the doomed morbidity that the passage of time reaps upon the human race, we are gifted with an inner life.

But nothing comes for free. The knowledge of death alone is a severe enough price to pay, but this is not our only debt. We may stand apart with the animals from the plant kingdom with our increased physical and mental mobility, but this means that we are uprooted – we must seek our own food and build our own shelters.7

And what an array of shelters we’ve erected in our time on this earth – huts, tipis, yurts, caravans, igloos, cottages, longhouses, roundhouses, canvas tents, ramadas, shacks, bunkers, sod houses, sheets of tin, sheets of iron, sheets of steel, palaces, castles, domes, barns, lean-tos, outhouses, log cabins… each of these shelters has a different roof. Upon each of these roofs, as if they were an assortment of differently-tuned drums, the music of the rain plays.

As a child I used to love visiting the family caravan in Wales because of how loud the rain sounded against the thin metal roof; it made the fire and the blankets warmer, and the small, cramped space larger. This is also my mother’s strongest memory of the times we spent there – that sound, the loud hush. Even the times when it wasn’t raining seem permeated now in retrospect with this sound, as if my memories of the place are all sheltered together in one remembered day, “brought together again in its water”. Being in a car while it rains gets even closer to the essence of this experience – the smaller the shelter, the greater the sense of communion that the rain provides. I have explored this sensation in a still-unpublished story:

“The prospect of rain was comforting. For all that she wanted to leave her nomadic life behind, she was not sure that she could ever live in houses the way other people did. She would miss the sound of the rain against her tent too much. When she heard that sound she felt as if the tent was an enormous pavilion extending to the very edges of the world, like a comfortable cat stretching out its body, and all and everything had come to sit inside with her around her little oil lamp, surrounded by her pots and pans. Listening to the rain fall against the tarp she felt welcomed by the universe.”

Over the past year, listening to the rain, I’ve found myself wanting to buy a hang drum.8 It’s an instrument I’ve loved the sound of for years, but only recently have I had the desire to play it. In my imagination I’m sitting in the middle of my living room, facing my window, watching it rain. My wrists loosen, I let my fingers fall gently into the steel hollows and ridges of the little dipping and rising tableland of music, doing as the rain does, forgetting myself. Some dreams want to become real. Music is one of those dreams.

Music and silence are two roads we can take towards a temporary forgetting of ourselves, of a merging with the world. Continuous noise that cannot be resolved by the mind into music or silence keeps us in a state of agitation, or of disquiet. Rain is one of the great silences. Fernando Pessoa, a paradox of a writer whose project was to forget himself by inventing many different personas whose anxieties he could occupy instead, shares this moment observing the rain from a window in The Book of Disquiet:

“Silence emerges from the sound of rain and spreads in a crescendo of gray monotony over the narrow street I contemplate. I’m sleeping while awake, standing by the window, leaning against it as against everything. I search in myself for the sensations I feel before these falling threads of darkly luminous water that stand out from the grimy building facades and especially from the open windows. And I don’t know what I feel or what I want to feel. I don’t know what to think or where I am.”

The downwards momentum of the inertia of rain dreams is embodied in this paragraph. Pessoa makes no effort of will, he is “leaning against [the window] as against everything.” His search within himself was doomed from the start – he is overcome by the rain, sleeping while awake.

An entire volume could no doubt be complied of writers and their characters at windows watching it rain, but since this is not that volume, I’ll settle for one more passage to set against Pessoa’s, written by a writer with an altogether more vital sense of self than the self-effacing Portuguese flaneur. In her novel Near to the Wild Heart, Clarice Lispector, in a typically incantatory style, writes:

“I’ve discovered a miracle in the rain… a miracle splintered into dense, solemn, glittering stars, like a suspended warning: like a lighthouse. What are they trying to tell me? In those stars I can foretell the secret, their brilliance is the impassive mystery I can hear flowing inside me, weeping at length in tones of romantic despair. Dear God, at least bring me into contact with them, satisfy my longing to kiss them. To feel their light on my lips, to feel it glow inside my body, leaving it shining and transparent, fresh and moist like the minutes that come before dawn. Why do these strange longings possess me? Raindrops and stars, this dense and chilling fusion has roused me, opened the gates of my green and sombre forest, of this forest smelling of an abyss where water flows. And harnessed it to night. Here, beside the window, the atmosphere is more tranquil. Stars, stars, zero. The word cracks between my teeth into fragile splinters. Because no rain falls inside me, I wish to be a star. Purify me a little and I shall acquire the dimensions of those beings who take refuge behind the rain.”

Lispector’s words burn with the desire for life, which she here directs at the stars, “those beings who take refuge behind the rain”. The stars are on the other side of the rain, she is dreaming through the rain. As Pessoa allows his inertia to carry him downwards, Lispector – always defiant in her brilliance – dreams upwards. No way up but through. Instead of the rain curtailing the path of her imagination, she uses it to enhance the poetry of the stars; the rain is not enough to ground her, instead she incorporates it into her celestial vision, it is in fact the ingredient that makes the vision potent, the current against which she swims.

There is a crystalline perfection to the night she describes – though there must have been clouds, she mentions only the stars and the rain, as if the rain was pouring directly from the same unclouded firmament in which they sat. In reality, when it rains we are often closed in under a dome of cloud. But the wet streets offer consolation, populating themselves with faux stars. In the sheen that coats the ground a reversal of the kind Charles Cros discovered in his dream casket happens – though not an inversion of interior and exterior, but of above and below. The miniature world of the rain-space puts on a display. Its lights are doubled and tripled – on the road, on the wet walls, on the roofs. Cities are in fact the perfect environments for the maximisation of this effect – I imagine an extra entry into Calvino’s magnificent collection of visions in Invisible Cities: a city designed in such a way as to allow the rain to gleam as attractively as possible from every surface. A composition of reflected light.

And why can’t a rainy street aspire to the nobility of a constellation? Because of time. Its lights are not fixed. It is just an illusion, a fanciful way of seeing – the gleaming street is only playing. But time is only playing at fixity too. Let the mock-constellations have their play. Let the puddles be portals for dreaming. To the imagination, reflections only multiply the avenues to be explored.

Also unable to be licked, for whatever that’s worth.

Though an episode of Tom & Jerry made a younger me believe that when you reach the end of the rain it simply stops like a sudden wall that can be walked through into dryness.

This may be a paraphrase – I can’t for the life of me find the page in the book to verify it.

Voltaire: “If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him.”

My first novel was dreamed while lying in a bed in Amsterdam as the rain fell on the canals outside.

Two of my favourite childhood rainy-day films, Toy Story 2 and Small Soldiers, now seem especially apt. And the quoted Bachelard/Cros passage really reminds me of the films of The Brothers Quay, who are also great dreamers and tinkerers of minutiae.

I give a more thorough examination of this topic in my essay The Human Animal.

Wanting, and not buying, because I have to think twice before buying a loaf of bread, never mind a hang.

Stunning. So many quotes about this liminal rain world that felt so satisfying to read, sentences whose forms were pleasing to my eyes and, when spoken aloud, my mouth. Sentences I wish I'd dreamt up.

As someone who moved from California to the United Kingdom on her own at the age of nineteen, because I love the rain and green, mossy places, this piece of writing felt like entering into the very rain dream state you described. I love the strange liminal world of rain.

The Clarice Lispector quote tasted so good I read it out loud several times. I have never heard of her and thank you kindly for the introduction - and for the introduction to Gaston Bachelard.

I'm realising that I'm growing into my worldview as an animist, rain is absolutely alive, endowed with personhood as Graham Harvey would say. Storms, too. And rain is not one entity. Rains in South East England are very different from rains in Glasgow, and even in the same place, one rainfall is not the same as another. Having said that, no sky is the same either but each is equally a person.

"Music and silence are two roads we can take towards a temporary forgetting of ourselves, of a merging with the world." I think you would love what the Sufis have had to say about music. "The whole process of the Sufi path – the fasting, retreats, renunciation, and *sama* – the listening and dancing to music – is to transcend the self or ego – the nafs. Over the course of the spiritual journey, the nafs is gradually burnt away until nothing of it remains, and only then can god appear. True selfhood lies in the experience of no self, of being nothing at all." Source: https://youtu.be/7xcBDg2JYkg?si=8SOPnHXJ2qfZlpga

"And yet, for all the doomed morbidity that the passage of time reaps upon the human race, we are gifted with an inner life." I do not think humans are the only beings gifted with an inner life but there are hours of conversation in that statement that cannot be condensed into a comment.

Beautiful.